Capitol Reef isn't just a park of stunning cliffs and arches — it's the story of a wrinkle in Earth's crust, a river that enabled life, and the people who called it home. This park truly blew me away.

But, what exactly is it?

Imagine baking a layer cake with each layer varying in color, density, and texture. Then, you wedge something under one side of the cake so its layers tilt up. That's the Waterpocket Fold.

Now, pour water on that for millions of years.

All of that water will wash away the softer layers, forming arches, valleys, canyons, and domes. This is Capitol Reef.

Scaling that out to the force of a tectonic-plate during a mountain-building event, that analogy, in reality, can be incomprehensible to picture. It's not too hard to imagine early settlers' being in similar awe as they trekked through this spectacular region.

A view of Ferns Nipple...a story for a another time.

A view of Ferns Nipple...a story for a another time.

But, why call it Capitol Reef? Settlers saw the white, Navajo Sandstone domes as looking similar to US capitol building domes. The term "reef" refers to the rugged and rocky terrain that made travel arduous and seemingly impenetrable — similar to how an ocean reef makes nautical travel dangerous.

Sounds like a good place to establish your livelihood, doesn't it? Well, actually yes, yes it was.

Members of the Latter-Day Saints wanted to expand their community in the mid to late 1800s. So, they looked westward to establish missions. In 1880, the first settlers moved into a particular valley in Capitol Reef and founded Fruita. Because of its easy access to the Fremont River and the heat that's reflected off of canyon walls to the soil, Fruita was a prime area for agriculture, especially fruit (hence the name Fruita). These settlers planted orchards containing apples, peaches, pears, plums, walnuts, and almonds — orchards that are preserved to this day.

While a pretty ideal microclimate to homestead, settler life was still challenging. The Behunin family, a family of fifteen who were one of the first settler families in the area, built the below sandstone cabin before moving further into the heart of the Fruita Valley. The family faced flash floods that washed out their crops and their cabin was only large enough for a handful of the family. The older boys of the family slept in a sandstone alcove and the older girls slept in a covered wagon box.

A settler cabin for a family of 15.

A settler cabin for a family of 15.

But these settlers also discovered that they weren't the first civilization to take advantage of Fruita Valley. An indigenous group referred to as the Fremont People — actual name is unknown — lived, hunted, and farmed in Capitol Reef from roughly 300 to 1300 CE. While their name and reason for disappearance is a mystery, you can still find their petroglyphs tucked away throughout the park.

You can find ancient petroglyphs throughout the park.

You can find ancient petroglyphs throughout the park.

As you can imagine, there is so much to see and understand. So, here's just a small dent into what Capitol Reef has to offer:

Gifford Homestead: the last private residence of one of the families who settled in Fruita. Orginal barn (front right) and home (back left) still stand today.

Gifford Homestead: the last private residence of one of the families who settled in Fruita. Orginal barn (front right) and home (back left) still stand today.

As you drive into the park, you're greeted with towering red cliffs standing guard. These immense, rocky fortresses maintain their position until the road opens up into a little Eden. In his reflective travel-log, American Places, author Wallace Stegner describes Fruita Valley as...

...a sudden, intensely green little valley among the cliffs of the Waterpocket Fold, opulent with cherries, peaches, and apples in season, inhabited by a few families who were about equally good Mormons and good frontiersmen and good farmers.

Presiding in this valley is the Gifford Homestead, the last private residence of one of the families who settled in Fruita. You can visit the original barn and buy pie from original family house. These pies are baked using fruit grown from the same orchards that the settlers cultivated.

The park's pie is a great way to end a hike.

The park's pie is a great way to end a hike.

If you ever visit Capitol Reef, these pies really are a can't miss experience. I tried peach and cherry and they were delicious.

Named after Joseph Hickman, an early advocate for protecting Capitol Reef.

Named after Joseph Hickman, an early advocate for protecting Capitol Reef.

Take a moderate, 2 mile round-trip hike to a 133ft long natural, sandstone bridge. Once just a wall (known geologically as a fin), its softer rock was eroded by water until it collapsed and became a bridge 65 million years ago. Geological bridges are, in fact, different than arches — a bridge requires constant flowing water that carves through the fin and an arch generally requires wind and rain to cut weak spots in the fin over time.

One of the arches in that park that you can stand on top of.

One of the arches in that park that you can stand on top of.

Cassidy Arch is named after notorious bank-robber Butch Cassidy. As you hike the 3.4 mile (round-trip) trail, you'll get an expansive view of the same area Cassidy and his gang used for hiding spots.

Cassidy Arch pictured to the right.

Cassidy Arch pictured to the right.

The hike's beginning ascent.

The hike's beginning ascent.

While the elevation gain is only a bit over 800ft (according to my Garmin), the majority of the hike is precarious and uphill, making it a more strenuous hike. It's definitely a rewarding trek, especially since you can stand on top of this arch.

Hikers in between Capitol Gorge's steep walls. You'll notice the waterpockets on the left wall.

Hikers in between Capitol Gorge's steep walls. You'll notice the waterpockets on the left wall.

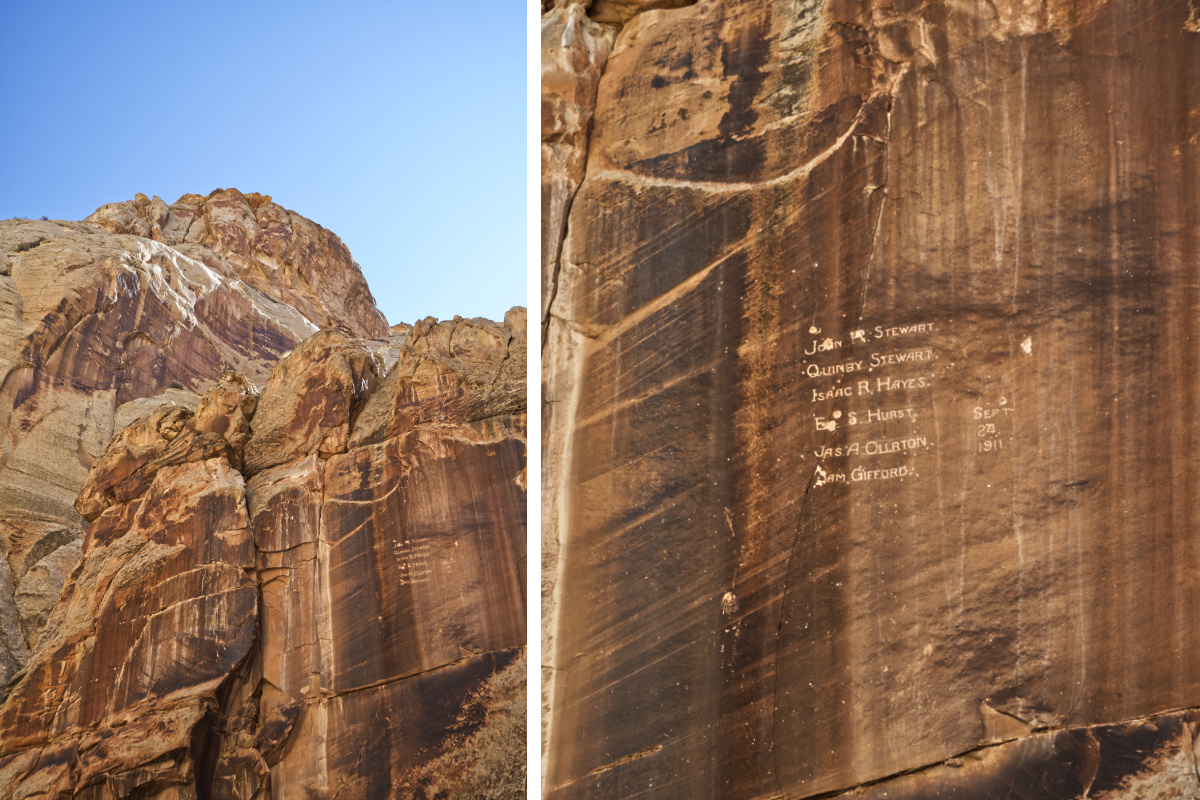

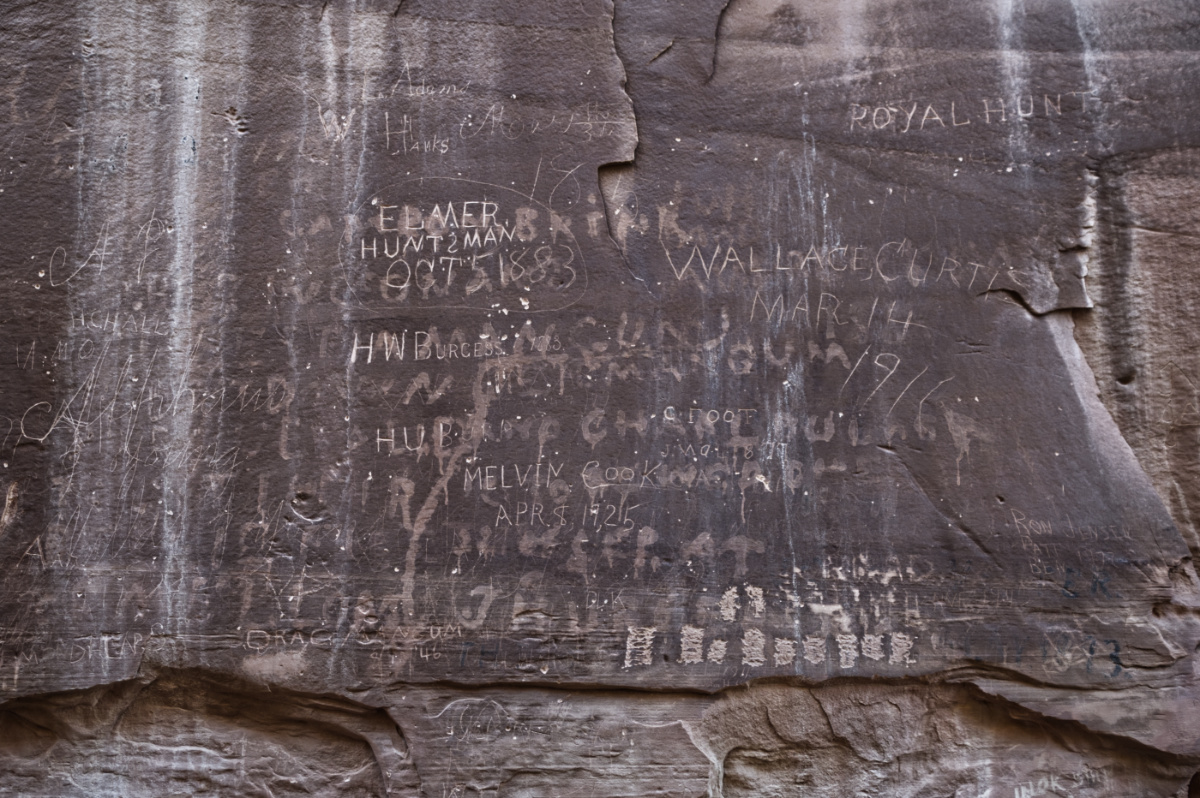

Before becoming an official trail in 1962, Capitol Gorge was a vital route for early pioneers. Some settlers who traveled through the Gorge left their mark in the Pioneer Register, leaving their names and the date.

These names were carved 50 ft above the Gorge's floor...as an erosion joke.

These names were carved 50 ft above the Gorge's floor...as an erosion joke.

Some etchings date back to the 1800s.

Some etchings date back to the 1800s.

The first couple of miles of Capitol Gorge are drivable, albeit with an all-wheel-drive vehicle. The road is not paved and has a couple rougher spots, but nothing too intense. The main factor is ensuring that conditions are dry and that the area is not at risk of flooding. You'll want to check the visitor's center for possible road closures.

You can drive through part of the unpaved Capitol Gorge road.

You can drive through part of the unpaved Capitol Gorge road.

If the area is open, I'd highly recommend adding Capitol Gorge to your stops. The experience is quite surreal and humbling. The names on the walls are real people who traveled this same path, facing tremendous hardships. These pioneers knew what they were doing was hard and was worth recording and celebrating.

Before traveling, I usually do some initial research on a destination's highlights, trying to quickly understand what my minimum itinerary should be. While helpful in gauging what gear to pack and setting up initial stops, the real goal of photographing a place is to tell its story when you get back.

In a massive place, like a National Park, that can be easy to forget. You're immersed in so much and you feel the urge to try to fit as much in as possible. It's easy to make the mistake that you can hop from one highlight to the next and you'll be able to capture it all — to feel like your quick survey did the place justice.

In reality, most locations require a fair amount of unplanned exploration time. This means building into your itinerary time to wander and commit to the random side-quests you stumble upon, even if that means you see "less" highlights. Only then can you start to experience, appreciate, and capture a place's character. Because of how interconnected almost every excursion is in Capitol Reef, this National Park was an excellent reminder to be present and allow a place to tell its own story without me applying my expectations on it.

And, many of these moments I simply can't capture. It's a surreal experience hiking the same trail that people, over a hundred years ago, traversed by foot and by wagon. It's just one of the incredible experiences that weaves together an otherwise inexplicable park.

I hope to return to this extraordinary place!